Unlocking Tau Protein: From Physiological Function to a Key Player in Neurodegenerative Diseases

In the study of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, a molecule named Tau protein remains a central focus of the scientific community. It acts as a "guardian" maintaining normal neuronal function but can transform into a "disruptor" causing neural damage under pathological conditions. This article systematically explores Tau protein from three dimensions—molecular structure, physiological function, and pathological changes—and its close relationship with human neurological health.

I. Tau Protein "Identity File": Structure and Distribution

Tau protein (official symbol: MAPT, Microtubule-Associated Protein Tau) was first isolated from porcine brain extracts by scientist Weingarten in 1975. Its gene is located on the long arm of human chromosome 17 (17q21). As a microtubule-associated protein (MAP), its core function is closely linked to microtubules—the intracellular "highways" and "structural bridges" responsible for material transport and maintaining cell shape in neurons.

Molecular Structure:

The amino acid sequence of Tau protein includes three key functional domains that determine its physiological role:

•Nterminal domain: Rich in acidic amino acids, it interacts with other neuronal proteins (e.g., neurofilaments, membrane components) to help stabilize neuronal morphology.

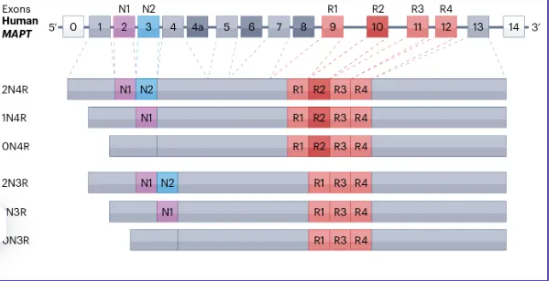

•Microtubule-binding domain (MBD): The core functional region, containing 3–4 repeat sequences (resulting from alternative splicing of mRNA). Six major Tau isoforms exist in the human brain (e.g., 0N4R, 1N4R, 2N4R, 0N3R, 1N3R, 2N3R), enabling specific binding to tubulin to promote microtubule assembly and stability.

•Cterminal domain: Contains phosphorylation sites and regulatory sequences, serving as a "switch" for intracellular signaling pathways that modulate Tau activity.

Tissue Distribution:

Tau is highly neuron-specific—under normal conditions, it is predominantly enriched in neurons of the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), especially within axons (the long fibers transmitting signals). Its expression is very low in peripheral tissues (e.g., liver, muscle), and its function there remains unclear.

II. Tau Protein at Work: Physiological Functions

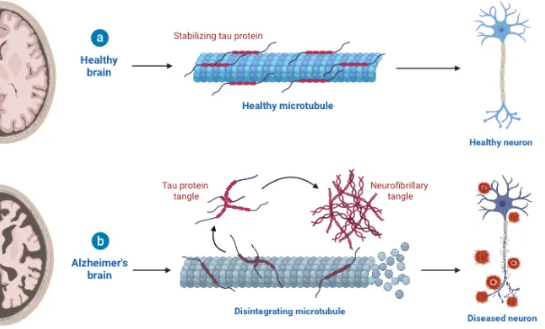

In healthy neurons, Tau’s core role is to maintain microtubule stability, supporting neuronal survival and signal transmission. Key functions include:

1.Microtubule Assembly and Stabilization

Microtubules (hollow tubular structures formed by α/β-tubulin polymerization) facilitate "cargo transport" in axons—moving proteins, mitochondria, and other nutrients from the cell body to axon terminals, and transporting waste back. Tau binds to tubulin or microtubules via its MBD, promoting polymerization and preventing depolymerization to ensure microtubule integrity.

Dysfunction or deficiency of Tau leads to microtubule disassembly, disrupted transport, and neuronal death.

2.Maintenance of Neuronal Morphology

Neurons have complex structures—cell body, dendrites (signal-receiving branches), and a long axon. Tau stabilizes the cytoskeleton (including microtubules) by enhancing their rigidity and elasticity, providing structural support. For example, in cortical pyramidal neurons, normal Tau expression is essential for maintaining long axons and intricate dendrites.

3.Regulation of Signaling Pathways

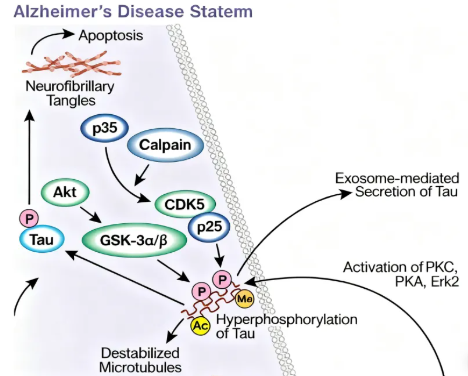

Beyond microtubule binding, Tau interacts with various signaling molecules (e.g., kinases, phosphatases, synaptic proteins) via its N- and C-terminal domains. It influences synapse formation and function by binding to postsynaptic density protein (PSD-95) and modulates neuronal survival/differentiation by regulating kinases like GSK-3β and CDK5.

III. Tau Protein Gone Awry: Pathological Changes and Disease Links

When Tau structure or function is impaired, it shifts from guardian to disruptor, triggering pathologies that lead to neurodegenerative diseases. The key pathological change is abnormal phosphorylation and the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs).

1.Core Pathology: Hyperphosphorylation and Aggregation

Normally, Tau phosphorylation is dynamically balanced—kinases (e.g., CDK5, GSK-3β) add phosphate groups, while phosphatases (e.g., PP2A) remove them.

In disease states (e.g., aging, gene mutations, oxidative stress), this balance is disrupted: hyperphosphorylation alters Tau’s conformation, reducing its affinity for microtubules. Detached Tau loses function and misfolds, forming insoluble oligomers that aggregate into paired helical filaments and ultimately NFTs.

NFT distribution is disease-specific: In Alzheimer’s, NFTs first appear in the entorhinal cortex (critical for memory), then spread to the hippocampus and cortex. Other tauopathies show distinct NFT patterns.

2.Toxic Effects on Neurons

•Microtubule collapse: Detached Tau fails to stabilize microtubules, disrupting transport and causing neuronal death.

•Toxic aggregates: Tau oligomers damage cell membranes, mitochondria, and synapses, inducing oxidative stress and inflammation.

•Prion like spreading: Misfolded Tau can spread between neurons via synapses, propagating pathology—a key reason for disease progression.

3.Associated Diseases: Beyond Alzheimer’s

Tau pathology is central to a class of disorders called tauopathies, including:

•Alzheimer’s disease: Characterized by amyloid plaques and NFTs.

•Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP): Affects midbrain/brainstem, causing eye movement deficits, postural instability, and cognitive decline.

•Corticobasal degeneration (CBD): Involves cortex/basal ganglia, leading to rigidity, motor slowing, and cognitive impairment.

•Frontotemporal dementia with Parkinsonism-17 (FTDP-17): Caused by MAPT mutations, featuring frontal/temporal atrophy and behavioral changes.

•Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE): Seen in individuals with repetitive head trauma, with Tau aggregates in cortex/deep nuclei, causing cognitive and mood disorders.

IV. Future Directions in Tau Research: Therapeutics and Diagnostics

Given Tau’s pivotal role, research focuses on three fronts:

1.Tau-Targeted Drug Development

•Inhibit hyperphosphorylation: Modulate kinase (GSK-3β, CDK5) or phosphatase (PP2A) activity.

•Block Tau aggregation: Develop small molecules (e.g., MTDLs) or antibodies to prevent oligomerization.

•Clear pathological Tau: Immunotherapies using anti-Tau monoclonal antibodies (e.g., gosuranemab, tilavonemab) are in clinical trials, showing promise in reducing Tau aggregates and slowing cognitive decline.

2.Tau-Based Diagnostic Technologies

•CSF biomarkers: Measuring phosphorylated Tau (e.g., p-tau181, p-tau217) in cerebrospinal fluid aids early Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

•TauPET imaging: Radioligands (e.g., flortaucipir) visualize Tau distribution in the brain, enabling precise disease staging.

3.Advances in Basic Research

Emerging insights include Tau secretion into extracellular spaces (e.g., blood, CSF) and isoform-specific roles (3R vs. 4R Tau) in different diseases, opening new avenues for subtyping and diagnosis.

Conclusion

The study of Tau protein mirrors humanity’s quest to understand neurological health and disease—from its initial identification as a "microtubule accessory" to its current status as a "key driver" of neurodegeneration. Each discovery deepens our insight into the brain’s mysteries.

To support researchers in this critical work, KELU Biotech offers a range of Tau-specific ELISA kits designed for accuracy and reliability. While Tau-targeted therapies are still evolving, advances in understanding its pathology and diagnostics inspire hope that effective treatments for tauopathies will emerge, bringing relief to millions worldwide.

For reliable Tau protein research tools, explore KELU Biotech’s ELISA products—engineered for precision and reproducibility.